For several decades, Kenya was seen as the big brother in Eastern Africa, with extensive diplomatic tentacles and allure throughout Africa.

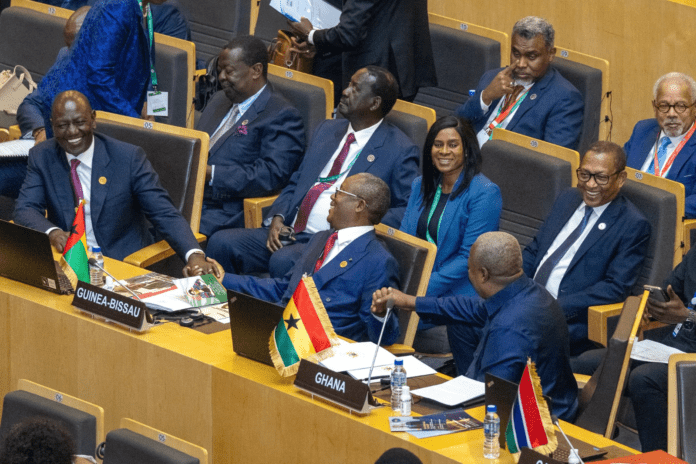

The recent loss by Kenya’s candidate, Raila Odinga, in the AUC election, despite the best effort and intention by the government, has however, raised several questions in the diplomatic circles, key among them being the cause of the country’s apparent waning of diplomatic influence in the continent.

The most surprising aspect of this loss was that a number of the East African Community countries did not vote for Raila despite the regional economic bloc having presented him as their own candidate.

While it can be argued that each country votes according to what they perceive as their most objective interest, the fact that these countries have not considered Kenya’s candidature in two successive AUC elections to be well-aligned with their national interests is a matter that should concern Kenyan authorities.

While there is good reason to blame Raila’s loss on regional, religious and linguistic considerations, and the immediate Eastern African regional political dynamics, it would definitely be naive to ignore Kenya’s country-specific factors. Some people have also mentioned the decampaigning by Gen-Zs and political formations,, but I think their influence, if any, on the outcome of the election was infinitesimal.

It will be recalled that in 2017, Kenya’s candidate for the same position, Amina Mohamed, lost by a large margin to the now outgoing Chairman, Faki Mohamed of Chad. Kenya’s repeated losses must therefore, be justifiably attributable to her own underlying internal diplomatic mis-steps and contradictions in the last two decades.

Kenneth Waltz, the founder of the neorealist theory of international relations, posits that a country can strengthen its influence by fostering a strong economy, investing in education and technology, promoting diplomatic relations, enhancing military capabilities, cultivating soft power and actively participating in international organizations, all while ensuring good governance and upholding human rights within its borders. All these factors boil down to the conundrum between a country’s internal capacity and projection of its external capability to muster diplomatic influence.

A country’s image and reputation play a significant role in its international influence. Evidently, Kenya is gradually losing its diplomatic grip even among some countries with which it shares historical colonial heritage, which suggests the country’s dimming international standing among its peers.

A realistic starting point for this analysis is the Eastern African region for, as the old adage goes, charity begins at home. Most of the countries within the EAC region appear to have one misgiving or another against Kenya.

Kenya’s military foray into Somalia was initially lauded as the most appropriate response to the unprovoked desecration of her territory by Isis, Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups that were operating from that neighboring country.

However, the continued stay of the military in Somalia without any hope of ever restoring lasting peace and security in that country has elicited negative sentiments, and caused huge backlash, with most locals now viewing it as an occupying foreign army. Kenya’s efforts in promoting peace and stability in regional conflicts through mediation have come a cropper.

The war in DRC has proven to be a huge headache within the Great Lakes region, as it has drawn in Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and South Africa, and threatens to engulf even more countries. Two successive Kenyan presidents, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, have miserably failed as negotiators in the war in DRC because of the perception that Kenya is complicit in the conflict.

In essence, Kenya has failed to pursue diplomatic engagements to build strong alliances with key allies and partners in order to create the requisite synergies for conflict resolution. Effective conflict resolution requires constructive dialogue and negotiations with all the parties to the conflict, and key stakeholders.

Pundits have opined that besides being suspected of complicity in the conflict, Kenya has not been patient enough to fully appreciate all the underlying dimensions of the DRC conflict. In the process, Kenya has proceeded with only partial understanding of the complexities of the war, hence the massive fallout that has caused phenomenal resentments against the country by multiple states within the EAC and South African Development Community (SADC) regions.

In recent years, Uganda which is Kenya’s biggest trading partner within EAC, has threatened to abandon its use of the Northern Transport Corridor that traverses Kenya, due to claims of unreasonable customs duty on goods and other hurdles at the Mombasa Port and along the way to Malaba border.

Tanzania is certainly conflicted in a number of ways. First, the country concurrently belongs to both EAC and SADC. But for reasons of its past leadership role in the liberation struggles of the Southern African countries under the framework of “Frontline States”, Tanzania tends to be more inclined to SADC than EAC.

Besides, there is a natural sibling rivalry between Tanzania and Kenya in terms of economic development, and the historical ideological conflicts that led to the collapse of the defunct EAC in 1977. The two countries have never recovered from that unfortunate event and the diplomatic spats that followed it.

To date, there is a simmering ‘cold war’ between Tanzania and Kenya, something that the former has never experienced with her SADC partners. The apparent rapprochement between Kenya and Rwanda means that Burundi, which has difficult relations with its twin-country, cannot fully embrace Kenya.

Further down, South Africa has never quite forgiven Kenya for its dalliance with the repressive apartheid regime at a time when most of the world had changed course against the De Klerk’s regime. It can be recalled, sadly, that the then Kenya’s president, Daniel Moi, was among the very last world leaders who openly visited apartheid South Africa in the regime’s dying days against world opinion.

As SADC’s largest economy, South Africa has a huge sway on all the countries of the region. It is therefore, not surprising that Kenya is not favored at all in the SADC region.

In spite of its relatively advanced economy, sophisticated education infrastructure, and proximity to SADC and other EAC countries, Kenya doesn’t enjoy commensurate cultural exchange programs with its neighbours.

Most of the educational and scientific collaborations from EAC and SADC flow to South Africa and Rwanda, indicating that Kenya is gradually losing its soft power in the Eastern and Southern African region.

With most of the EAC and SADC countries harboring resentments towards Kenya, it is very difficult for the country to get strong regional support required to catapult it to continental prominence and acceptability. Equally, there have been misgivings by African countries about Kenya’s prominent role in providing global leadership on issues of climate change.

The argument has been that Africa faces unique challenges with regard to climate change and adaptation, which ought to be addressed using equally unique approaches. Kenya has been accused of rushing to uncritically embrace generalized climate mitigation tools that are largely applicable to the industrialized world context.

Last but not least is the question of good governance, which is still a big concern in Kenya. The Constitution of Kenya 2010 created many institutions that were meant to engender good governance by protecting democracy and human rights, combating corruption, and promoting rule of law, transparency and social development.

Unfortunately, the institutions have remained, for the most part, unresourced and weak, and largely beholden to the Executive. The protection of civic liberties, as envisaged by the constitution, remains work-in-progress.

In the circumstances, Kenya’s diplomatic overtures, however well-meaning, cannot amount to much in a continent where more than 70 percent of the population is youthful, and extremely resentful of government intrusion into their private spaces.

What can Kenya do to reverse the free fall of her fortunes? Kenya is not short of qualified diplomats. Sadly, there is a penchant for mismatching personnel and roles. Kenya cannot afford to continue misfiring on diplomatic issues while expecting the aggrieved countries to clap their hands in approval. That will not happen.

Let Kenya commit itself to alleviating the needless diplomatic goofs by deploying suitably qualified personnel on critical roles.

Equally, the country must work on reversing the perception that the it is becoming increasingly intolerant of divergent opinions. The rest will be consequential.

Professor Ongore is a Public Finance and Corporate Governance Scholar based at the Technical University of Kenya